The Path to the Presidency

Introducing From David’s Desk, a new newsletter penned by Carlyle Co-Founder and Co-Chairman David M. Rubenstein and other leaders across our firm. Each edition provides insights on public policy, geopolitics, and other topics in and around Washington, DC.

Over the past few months, in light of my service in the Carter White House and my new book on the Presidency—The Highest Calling—I have been responding to many inquiries about the upcoming Presidential election. I thought those who have not already heard my thoughts might be interested in reading about them, and thus this new newsletter. I will continue to write about these, and other public policy, financial and geopolitical matters, in future editions.

With that lead-in, I might have misled you into thinking that I know who the next President will be. I do not. But nor do the professionals in each of the Harris and Trump campaigns. Nor do the journalists covering the campaigns. Nor do the professional pollsters. Nor the financial backers and donors who have spent so much of their funds backing a candidate they hope will win.

In my half-century in Washington, I have lived through, followed closely, or participated in thirteen Presidential campaigns. Of all those, this one has the most unclear outcome a few weeks before the election. And that is because, in brief, the country is honestly split down the middle between those who see Donald Trump as a strong political leader prepared to fight for America’s interests at home and abroad, despite the legal challenges and the, at times, blemished track record, and those who see Kamala Harris as the embodiment of traditional—and some new—Democratic principles and ideals (with the additional plus of being the first woman to become President and the person who can prevent Donald Trump from a second term—a high priority for her supporters).

Over the past half-century, political polling has become quite sophisticated and is generally quite accurate—within the so-called “margin of error.” National political polling generally consists of asking approximately 1500 individuals their views, and if these individuals are selected in ways that ensure they are roughly representative of the population, then the poll’s outcome is within a margin of error of roughly two-to-three percent. Of course, in a close election, a few percentage points is a potentially important and meaningful difference.

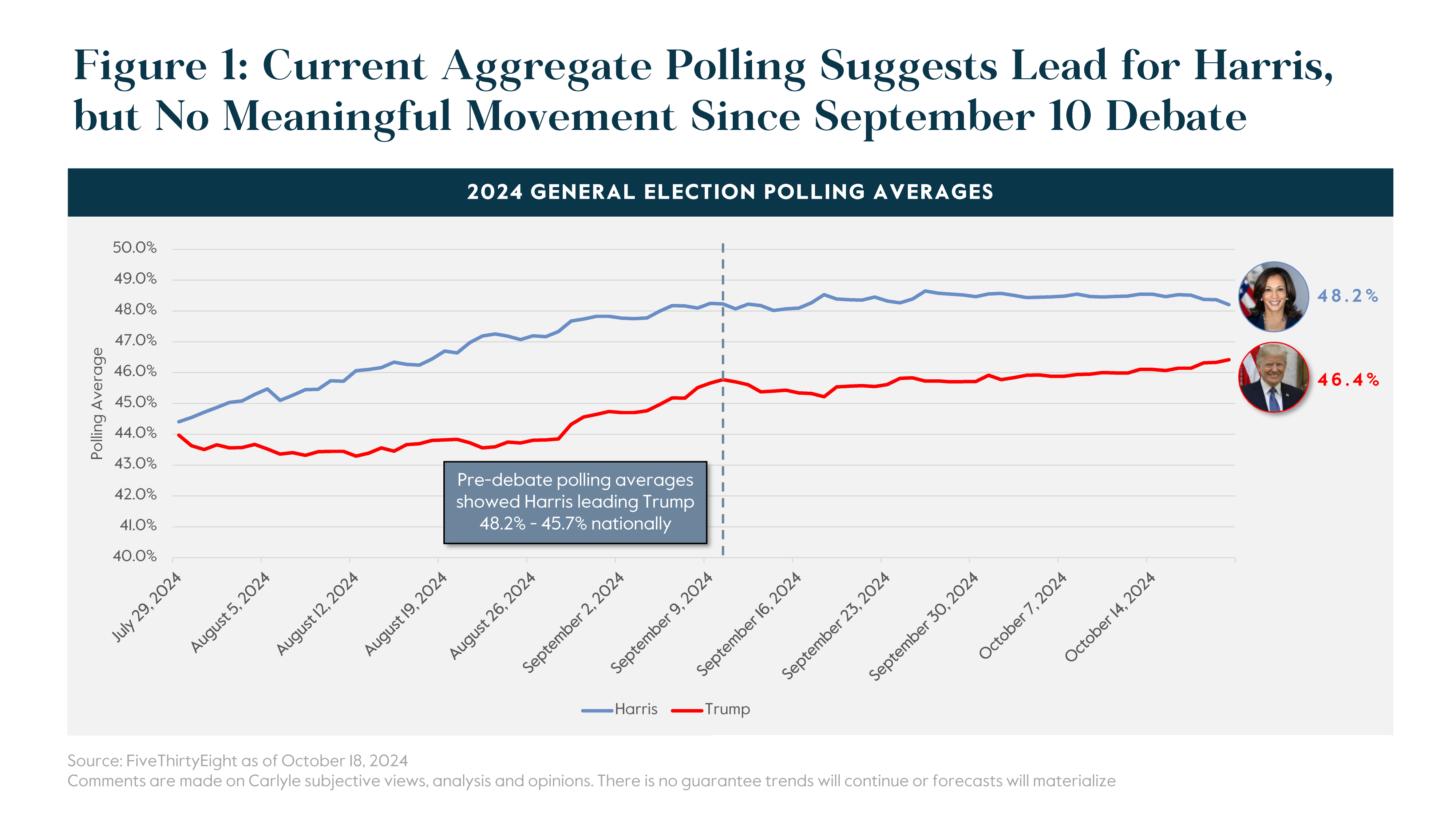

The polling community has never seen such consistently close outcomes between the two major political parties’ candidates—the various national polls show each candidate being roughly one or two points ahead of the other candidate—and that is within the margin of error (Figure 1). This means the poll outcome could be wrong by several percent in reflecting the sentiments at the time the poll was taken.

And of course, whether one candidate is ahead of another candidate by one or two points is not all that relevant, for the President is elected not by a nationwide popular vote—which is what the national polls reflect—but by the popular vote winner in each state. Each state has Electoral College votes to its population. There are 538 potential Electoral College votes, and 270 are required to win. The Electoral College was devised by the Founding Fathers, and placed in the Constitution, because at that time they did not believe the American population was sufficiently informed to make an appropriate Presidential election decision. The electors were to be “informed” citizens from each state. Now, the electors are generally politically active individuals representing their respective parties, and as a result of a recent Supreme Court ruling, the electors can be bound to vote for a state’s popular vote winner (except for Maine and Nebraska, where the states’ Electoral College votes reflect the state’s popular vote winner as well as the popular vote winner within each state’s Congressional districts).

So, what does this really mean? It means the focus should not be on the nationwide popular vote—in five elections the popular vote winner was not elected President—but on the vote in each state. Donald Trump became President as a result of the 2016 election, even though he had roughly three million fewer popular votes than Hillary Clinton.

So, what are the possible scenarios?

To put this in context, 45 of the 50 states voted Republican or Democratic in both 2016 and 2020 (they did not flip from one party to another). It is likely these states will again follow their pattern of consistently voting Democratic or Republican. There are five states—Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Georgia and Arizona—which voted in 2016 for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton but voted in 2020 for Joe Biden over Donald Trump. These are the so-called “swing states.” These states have between them 71 electoral college votes, and if Trump or Harris were to win all of these states—as Trump did in 2016 and Biden did in 2020, he or she would be the winner of the election. It seems unlikely that Trump or Harris will win all five of these states.

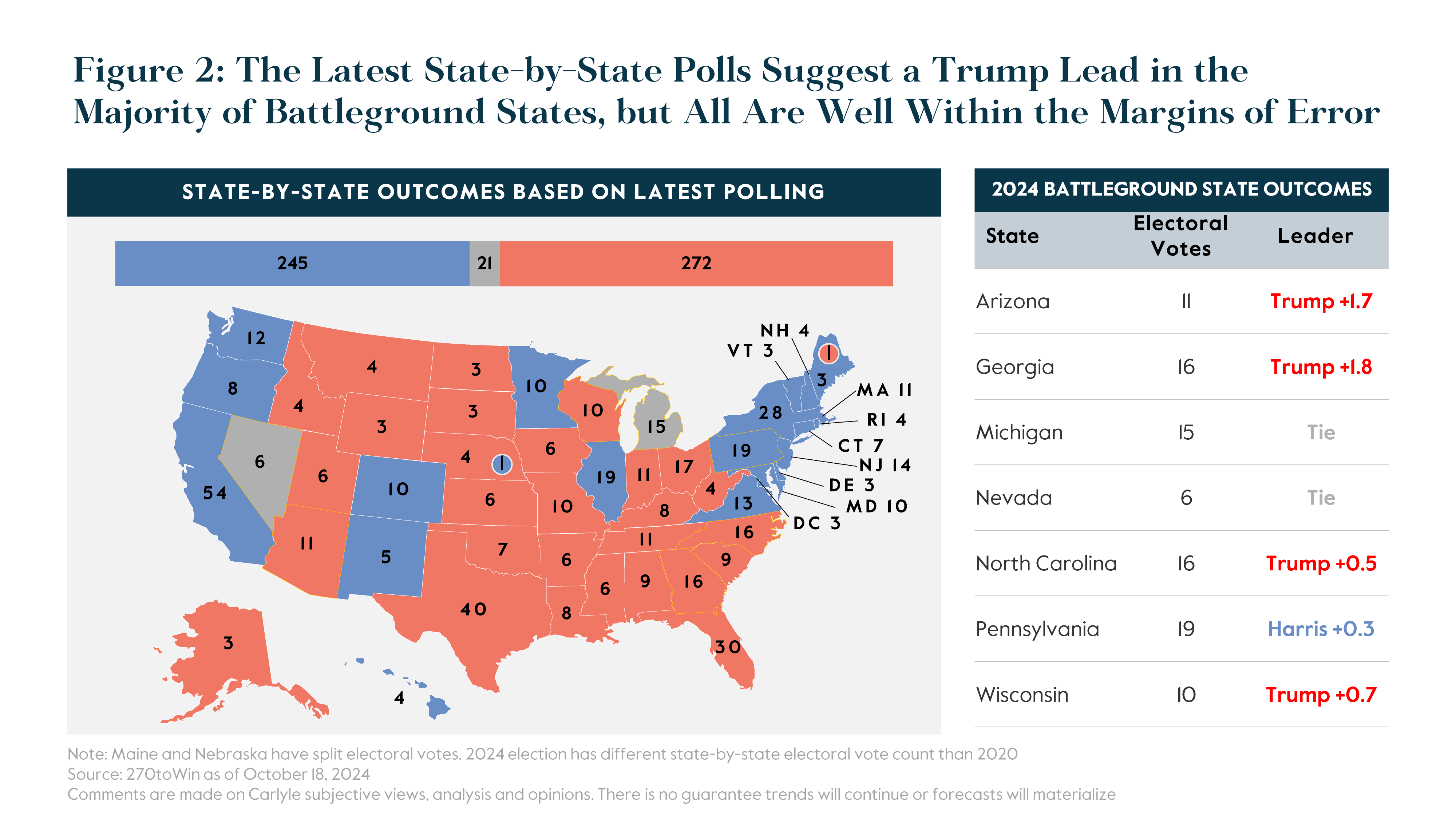

The polling data in each of these states is also “within the margin of error,” which is to say that all of these states could go either way (Figure 2). Of course, polling data in these—and other states—does not take into account exactly who will actually vote (as opposed to a voter’s preference). The last Presidential election had just below 160 million total voters, but roughly 80 million eligible voters did not vote. And thus, a great deal of both parties’ efforts now is not so much focused on convincing someone to vote for their candidate, but to get their known or likely supporters to actually vote. (And early voting has already begun in many states).

In addition to the five swing states, there are two other states that each party hopes to “swing”: (1) Nevada, which has voted Democratic in the last four Presidential elections, and (2) North Carolina, which has voted Republican in the last three elections. Republicans think they can swing Nevada, and Democrats think they can swing North Carolina.

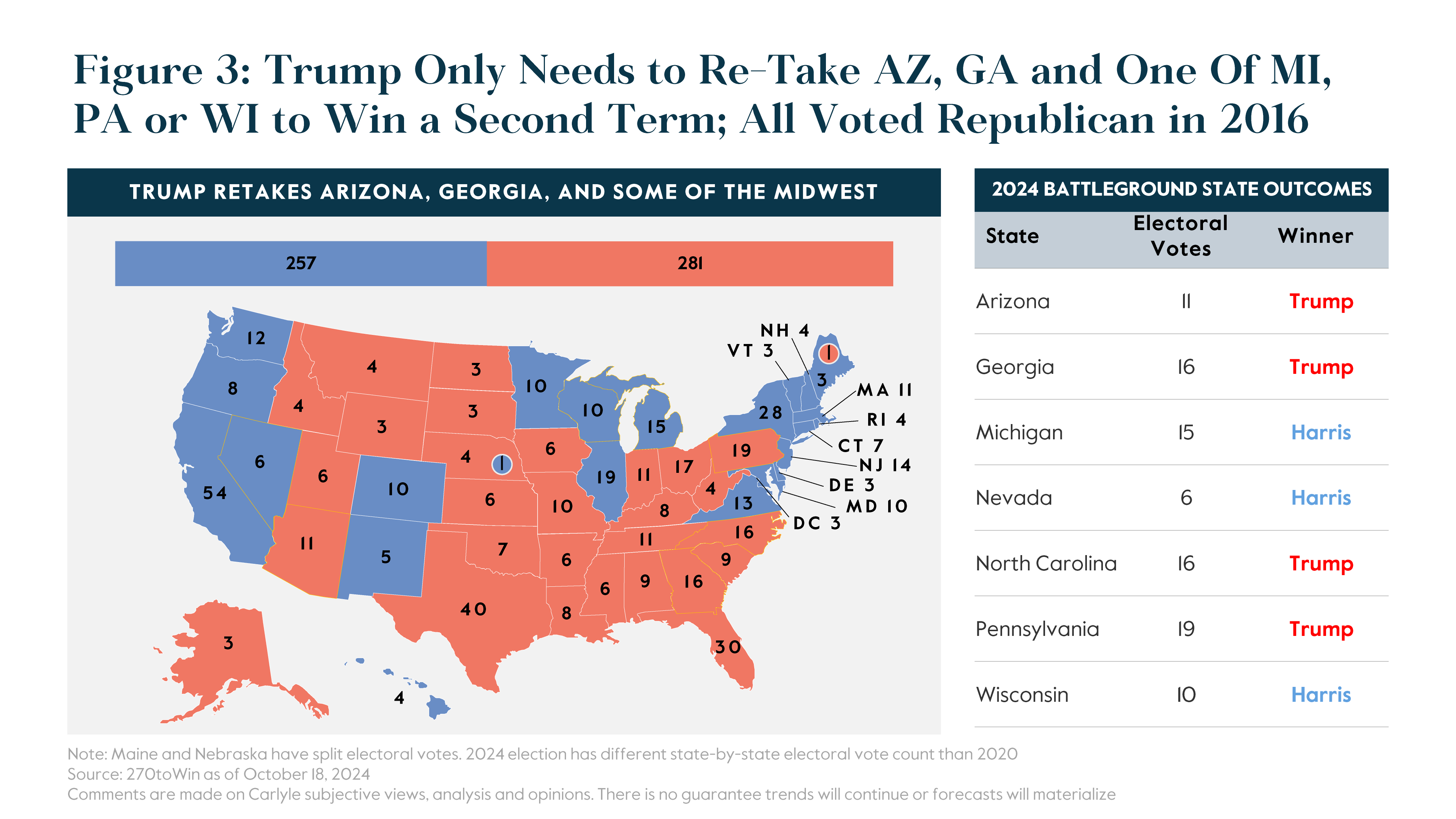

But to make the analysis simple, assume Nevada and North Carolina vote as they have in the past two elections. Just focus on the five swing states. If Trump wins Georgia and Arizona, he will become President if he also wins Pennsylvania (Figure 3). If Harris wins Michigan and Wisconsin, she will become President if she wins Pennsylvania or both Georgia and Arizona (or North Carolina, assuming Nevada stays Democratic). In short, Harris needs to win Pennsylvania (and keep Michigan and Wisconsin), and Trump needs Pennsylvania (assuming no change in North Carolina and he wins back Georgia and Arizona).

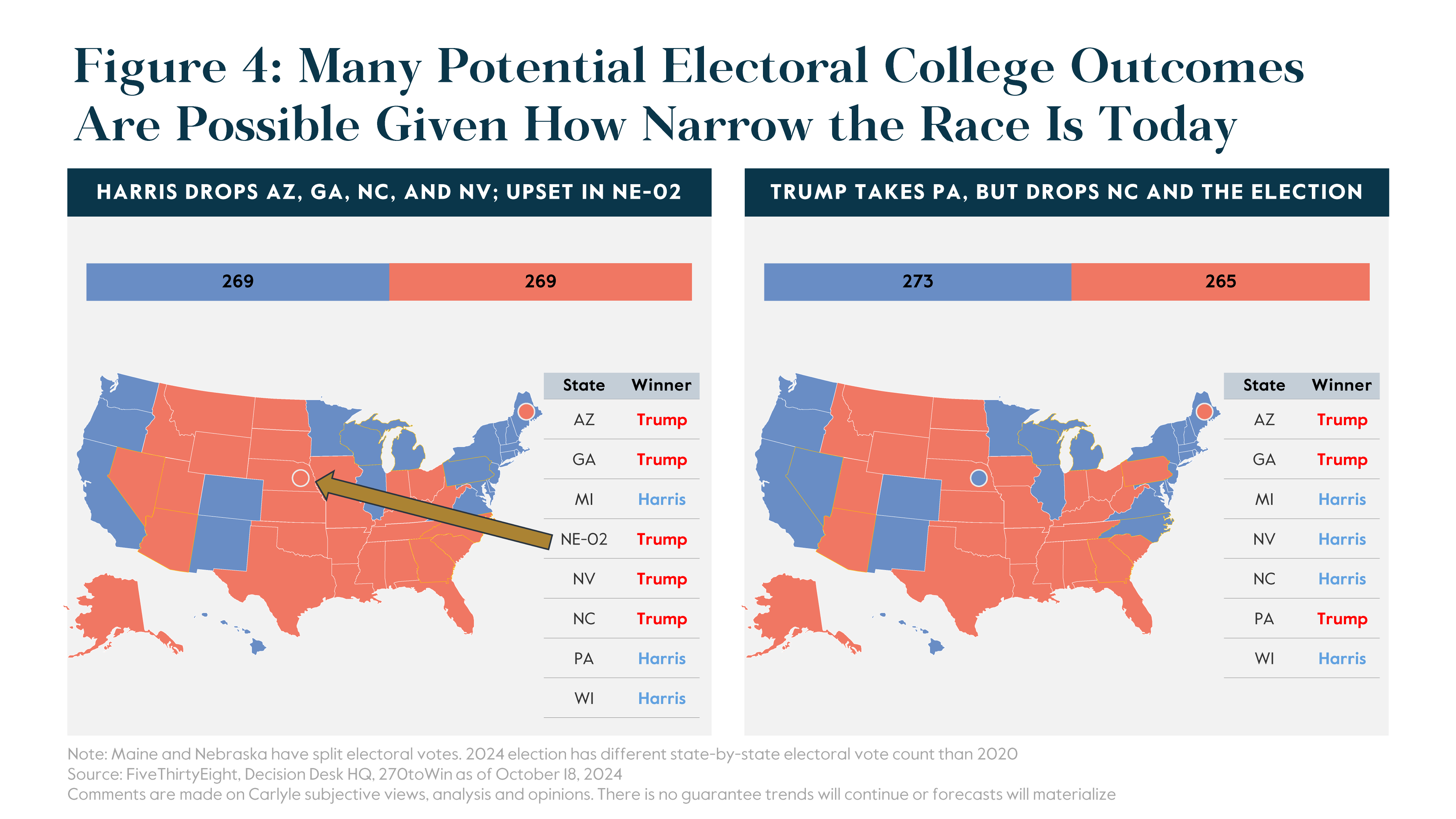

For these reasons, the focus of both campaigns is now heavily on Pennsylvania (Figure 4). Current polling is showing Harris or Trump ahead, depending on the poll, by one or two percent—not that meaningful at this point. Some are even showing a tie.

So, what are the Trump and Harris campaigns doing to win Pennsylvania? Trump is focusing his attention on non-college educated white men in central Pennsylvania—they are generally very supportive of Trump, but he needs to get them to vote. For that reason, Trump has done a number of rallies in Pennsylvania, one recently in Butler, the site of the assassination attempt, with supporter Elon Musk as an additional draw. And Harris is focusing on women and minorities in Philadelphia and its suburbs (black voters are the most consistently supportive ethnic group for Democratic Presidential candidates), and she is doing what she can to encourage them to actually vote. Harris has had her best surrogates—President Obama and Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro—working the state for her. In hindsight, had Kamala Harris picked Governor Shapiro as her vice-presidential candidate, it seems more likely that the state would vote for her, freeing up time to focus on other states, but hindsight is always 20/20.

Whatever the ultimate outcome of the election, it is likely to be a nail biter, and the outcome is unlikely to be known on election night. (Pennsylvania does not begin counting mail-in ballots until election day.)

Of course, it would be preferable to know who the next President will be on election night. That is almost certainly a pipe dream. If the election is close, legal challenges can be expected by both parties. And then there is the whole process of officially certifying the election. There is now talk in Washington that the current Speaker of the House, Mike Johnson, a loyal Trump supporter, might work with Senate Republicans to find a way to not certify the election if the outcome were to be a Harris victory, for he will likely be under enormous political pressure—assuming a close election—to do so.

In short, do not expect to know the election outcome for a while.

Of course, there are also the Congressional elections. Thirty-four of the one hundred Senate seats are having elections, as are all 435 of the House seats.

At the moment, the Democrats control the Senate by one vote, but they will have a hard time holding on to that majority, for Senator Manchin (WV) will almost certainly be succeeded by his state’s Republican Governor, and the Democratic Senator from Montana, John Tester, is an underdog to his Republican challenger (in a state where Trump is very popular).

In the House, currently under Republican control by two votes, the conventional wisdom is that the Democrats, because of redistricting and some gerrymandering, have a good chance of picking up seats and becoming the majority party in the chamber. But this is also too hard to predict. There are about 27 House seats that are viewed as “toss-ups” at the moment, and the outcome of those seats—not yet knowable—will likely determine who controls the House.

Of course, for the United States, the best outcome is surely a reasonably prompt outcome, for the uncertainty about the country’s political leadership cannot be a plus for the financial markets or for the outcome of geopolitical challenges now facing the US in the Middle East and Russia-Ukraine, not to mention China-Taiwan. (For what it might be worth, in the past few weeks, various betting sites seem to be assuming a Trump victory, though with no greater information than anyone else really has.)

There is a natural tendency to want to know the outcome of the elections, so planning for life under the new government can begin as quickly as possible. Nothing is wrong with that. But everyone should recognize that new administrations do not take office until January 20 of the following year, and there is more than enough time to plan for how the new Administration will govern.

Whoever is elected, a fair number of familiar faces can be expected around the White House. While some who served with President Trump before are unlikely to do so again, there are more than a few senior officials from the previous Trump Administration who will want to serve their country again and may seek similar kinds of positions, though there will inevitably also be some new faces. President Trump does not lack for supporters, and he will inevitably have a reasonably wide choice of individuals to serve under him. The jockeying for senior roles has already started.

By the same token, a new President Harris will probably keep a number of those who served in the Biden Administration, though in different positions in some cases. And she will no doubt bring back into government many who served under President Obama, to whom she is close, but who do not currently serve under President Biden.

I have been wrong before, and the election might not be as close as I currently believe, and we might know the outcome on election night. But that is not a bet I would make.

Whoever is President will have these challenges at the outset—assuming that the decision about who is elected President is peacefully resolved within at least a few weeks post-the election: (1) dealing with the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East; (2) establishing a workable relationship with China; (3) creating a tax bill to deal with the large tax cuts due to expire next year; (4) keeping the economy on an even keel (and avoiding a recession); (5) needing to replenish military equipment and supplies (a great deal of which has been sent overseas to help allies in current wars; (6) trying to get a budget organized which makes an effort to stabilize, if not reduce, the large level of the federal deficit; and (7) helping the US to maintain its lead in technological advancements, especially AI.